AlphaFold’s new rival? Meta AI predicts shape of 600 million proteins

Microbial molecules from soil, seawater and human bodies are among the planet’s least understood.

Ewen Callaway | 2022/11/01

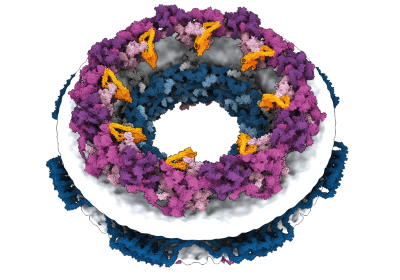

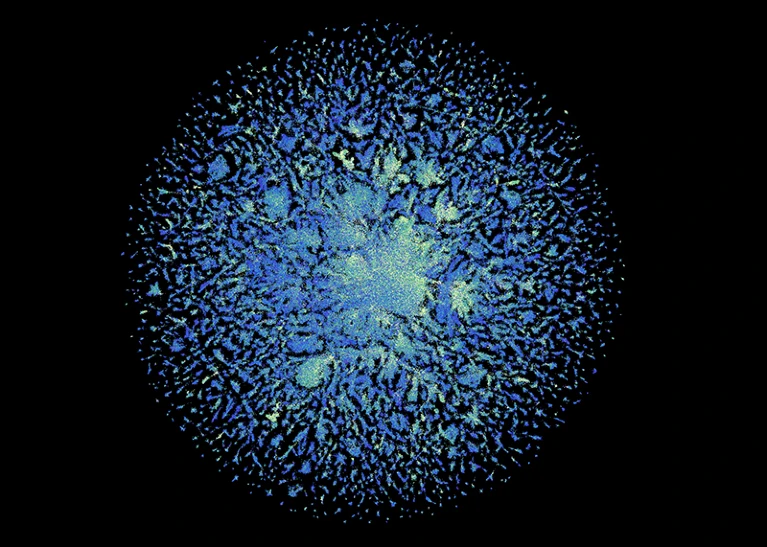

The ESM Metagenomic Atlas contains structural predictions for 617 million proteins. Credit: ESM Metagenomic Atlas (CC BY 4.0)

The ESM Metagenomic Atlas contains structural predictions for 617 million proteins. Credit: ESM Metagenomic Atlas (CC BY 4.0)

When London-based artificial-intelligence (AI) company DeepMind unveiled predicted structures for some 220 million proteins earlier this year, the trove covered nearly every protein from known organisms in DNA databases. Now, another tech giant is filling in the ‘dark matter’ of the protein universe.

Researchers at Meta (formerly Facebook, headquartered in Menlo Park, California) have used AI to predict the structures of some 600 million proteins from bacteria, viruses and other microorganisms that haven’t been characterized.

“These are the structures we know the least about. These are incredibly mysterious proteins. I think they offer the potential for great insight into biology,” says Alexander Rives, the research lead of Meta AI’s protein team.

The scientists generated the predictions — described in a 1 November preprint1 — using a ‘large language model’, a type of AI that can predict text from just a few letters or words.

Normally, language models are trained on large volumes of text. To apply them to proteins, Rives and his colleagues instead fed the AI sequences of known proteins, which can be written down as a series of letters, each representing one of 20 possible amino acids. The network then learnt to fill in the sequences of proteins in which some of the amino acids were obscured.

Protein ‘autocomplete’

This training imbued the network with an intuitive understanding of protein sequences, which contain information about their shapes, says Rives. A second step — inspired by DeepMind’s pioneering protein-structure-predicting AI, AlphaFold — combines such insights with information about the relationships between known protein structures and sequences, to generate predictions.

Meta’s network, called ESMFold, isn’t quite as accurate as AlphaFold, Rives’ team reported earlier this year2, but it is about 60 times faster at predicting structures for short sequences, he says. “What this means is that we can scale structure prediction to much larger databases.”

As a test, the researchers unleashed their model on a database of bulk-sequenced ‘metagenomic’ DNA from environmental sources such as soil, seawater and the human gut and skin. The vast majority of the entries — which encode potential proteins — come from single-cell organisms that have never been isolated or cultured and are unknown to science.

In total, the team predicted the structures of more than 617 million proteins. The effort took just two weeks (by contrast, AlphaFold can take minutes to generate a single prediction). The structures are freely available for use, as is the code underlying the model, says Rives.

Of the 617 million predictions, the model deemed more than one-third to be high quality, such that researchers can have confidence that the overall protein shape is correct and, in some cases, can discern atomic-level details. Millions of these structures are entirely unlike anything in the databases of protein structures determined experimentally, or any of AlphaFold’s predictions from known organisms.

A large chunk of the AlphaFold database is made up of structures that are nearly identical to each other, whereas metagenomic databases “should cover a large part of the previously unseen protein universe”, says Martin Steinegger, a computational biologist at Seoul National University. “There’s a big opportunity now to unravel more of the darkness.”

Sergey Ovchinnikov, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, wonders about the hundreds of millions of predictions that ESMFold made with low confidence. Some might lack a defined structure, at least in isolation, whereas others might be non-coding DNA mistaken for protein-coding material. “It seems there is still more than half of protein space we know nothing about,” he says.

Leaner, simpler, cheaper

Burkhard Rost, a computational biologist at the Technical University of Munich in Germany, is impressed by the combined speed and accuracy of Meta’s model. But he questions whether ESMFold really offers an advantage over AlphaFold’s precision when it comes to predicting proteins from metagenomic databases. Language-model-based prediction methods — including one developed by his team3 — are better suited to quickly determining how mutations alter a protein’s structure, which is not possible with AlphaFold. “We will see structure prediction become leaner, simpler, cheaper, and that will open the door for new things,” he says.

DeepMind doesn’t currently have plans to include metagenomic structural predictions in its database, but hasn’t ruled out adding them to future releases, according to a company representative. But Steinegger and his collaborators have used a version of AlphaFold to predict the structures of some 30 million metagenomic proteins. They are hoping to find new kinds of RNA virus by looking for previously unknown forms of the viruses’ genome-copying enzymes.

Steinegger sees trawling biology’s dark matter as the obvious next step for such tools. “I do think we will quite soon have an explosion in the analysis of these metagenomic structures.”

Nature 611, 211-212 (2022)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03539-1

References

Lin, Z. et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.20.500902v2 (2022).

Lin, Z. et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.20.500902v1 (2022).

Weissenow, K., Heinzinger, M. & Rost, B. Structure 30, 1169–1177 (2022). Article | PubMed | Google Scholar